The Clarity Trap

Understanding the Industry's Misdirection

Walk into any security procurement meeting across the industry, and the conversation follows a predictable pattern. The discussion begins with resolution specifications: "We need 4K cameras for better detail capture." It escalates to low-light performance: "What's the minimum illumination for clear night vision?" Compression algorithms enter the debate: "What codec provides the best quality at manageable bitrates?" Artificial intelligence features are presented: "Our system includes intelligent video analytics for automatic threat detection." Frame rates are discussed: "We recommend 30 fps for smooth playback."

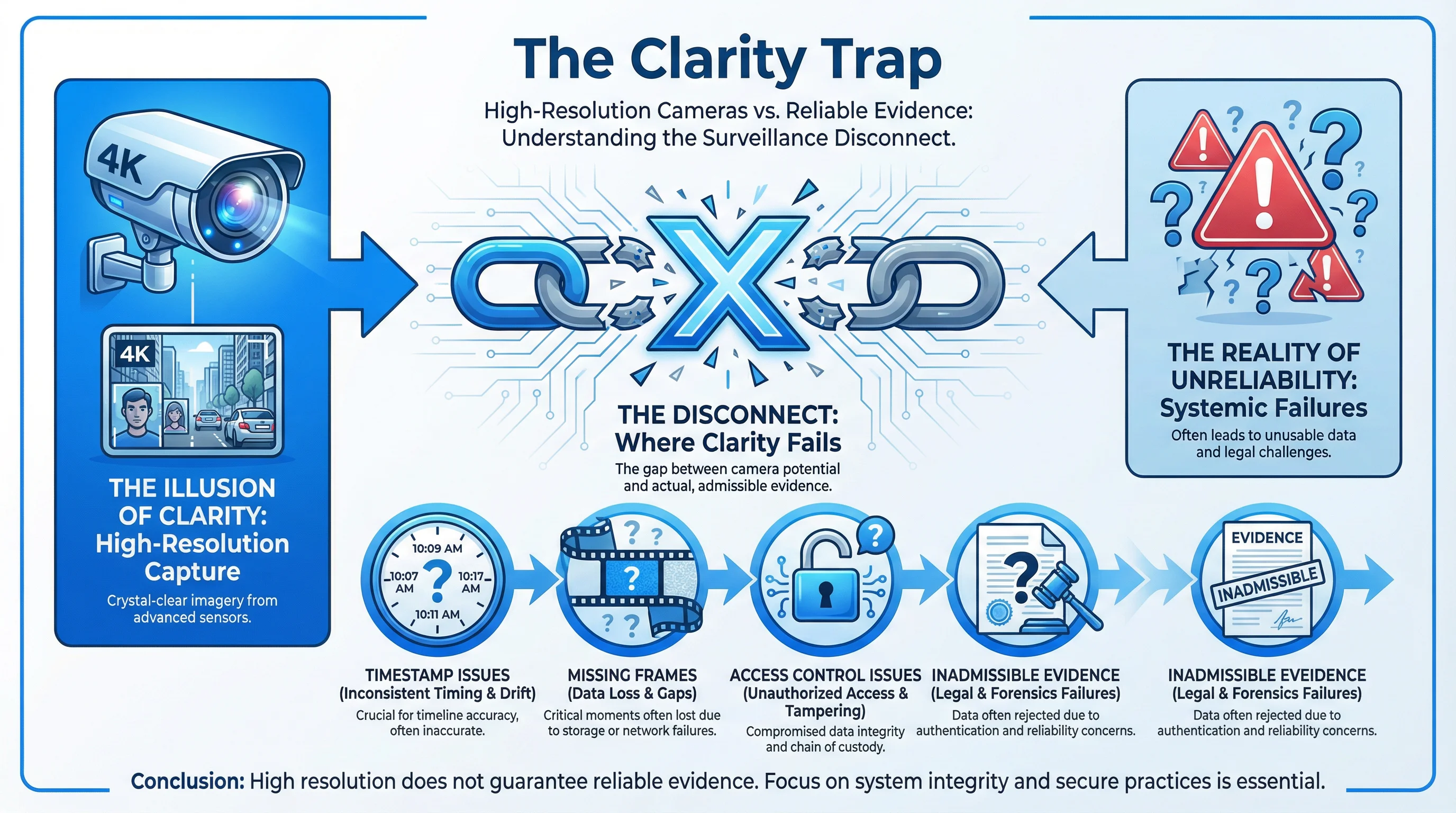

Yet in these comprehensive technical discussions, a critical question is almost never asked: "Can this footage be trusted as evidence?"

This omission represents one of the most consequential blind spots in modern security system procurement and deployment. The industry has optimized for observation—the ability to see what happened—while largely neglecting verification—the ability to prove what happened. These are fundamentally different objectives, and they require fundamentally different technical approaches.

Six Common Misconceptions

The clarity trap manifests through six persistent misconceptions that shape purchasing decisions, system designs, and operational practices:

Misconception 1: Resolution and Frame Rate Guarantee Usability

The assumption is straightforward: higher resolution captures more detail, and higher frame rates provide smoother motion. Therefore, a 4K system at 30 fps should be superior to a 1080p system at 15 fps. This logic fails when footage reaches the moment of truth—when it must be used as evidence.

A 4K image that cannot be proven unaltered is merely a high-resolution picture. A 1080p image with complete timestamp verification, integrity checksums, and documented chain of custody is evidence. When a dispute arises, the admissibility of the footage depends not on its resolution but on whether it can be proven authentic. A system that captures beautiful but unverifiable images has optimized for the wrong metric.

Misconception 2: "Playback Capability" Equals "Usable Evidence"

Many systems can replay footage—the ability to retrieve stored video and view it on a screen or in an application. This is conflated with evidence usability. The distinction is critical: playback proves the system stored something; it does not prove what was stored is authentic or complete.

A system might successfully replay footage while simultaneously suffering from undetected frame loss, timestamp inconsistencies, or unauthorized access. The ability to play back video is a baseline feature, not a guarantee of integrity. True usability as evidence requires proof of completeness (no missing frames), proof of authenticity (no modifications), and documentation of the entire access and handling history.

Misconception 3: Long Storage Duration Ensures Evidence Preservation

Extended storage capacity—"We can retain footage for 90 days"—is presented as a strength. Yet storage duration without integrity protection is a liability. Footage stored for 90 days without write protection, without integrity checksums, and without access auditing is not preserved evidence; it is a target for tampering.

A malicious insider, a disgruntled employee, or an external attacker with system access can modify, delete, or selectively corrupt footage. If the system provides no mechanism to detect such tampering, the stored footage's evidential value is compromised. Long-term storage without long-term integrity verification creates a false sense of security.

Misconception 4: Mobile App Access Satisfies Audit Requirements

The convenience of viewing footage through a mobile application is presented as a feature. Yet this convenience, without accompanying audit controls, undermines evidence integrity. If anyone with credentials can access, download, and share footage without logging, without approval workflows, and without creating an audit trail, the evidence chain is broken.

True audit capability requires not just the ability to access footage but comprehensive logging of every access: who viewed what, when, for how long, and what actions they took. It requires role-based access controls that limit who can export footage. It requires approval workflows for sensitive operations. A system that allows unrestricted mobile access without these controls has sacrificed evidence integrity for user convenience.

Misconception 5: "Footage Exists" Means "Footage Is Complete"

The assumption that stored footage is complete—that every frame from the relevant time period is present—is rarely verified. Footage may appear continuous during playback while suffering from undetected frame loss, dropped packets, or buffer underruns. These gaps may be microseconds or seconds, but they create discontinuities in the evidence chain.

In a critical investigation, these gaps become liabilities. An attorney can argue that missing frames could contain exculpatory or incriminating evidence. A forensic expert can testify that the footage is incomplete. The system must be designed to detect, log, and alert on any discontinuity in the video stream. Completeness must be verifiable, not assumed.

Misconception 6: Export Capability Means Export Reliability

Many systems can export footage in common formats—MP4, AVI, or proprietary containers. This export capability is presented as sufficient for evidence use. Yet exported files without metadata, without integrity verification, and without standardized formats are problematic as evidence.

When footage is exported, the exported file must include metadata (original capture time, device identity, storage location), must include cryptographic verification (checksums or digital signatures), and must be in a format that can be independently verified. Without these elements, an exported file can be challenged as potentially modified. The export process itself must be logged and auditable. Export capability without these safeguards is not evidence-ready export.

The Real Cost of These Misconceptions

These six misconceptions combine to create systems that excel at observation but fail at evidence provision. The consequences emerge when footage is actually needed:

In Disputes: A property damage claim is filed. The surveillance footage clearly shows the incident, but the timestamp is off by several minutes due to lack of time synchronization. The insurance company questions whether the footage is from the claimed incident or a different time. Without timestamp verification, the claim becomes disputable.

In Investigations: A theft occurs. The footage shows a person entering the secure area, but there is no audit log showing who accessed the footage, when, or for how long. The defense attorney argues that the footage could have been selectively edited or taken out of context. Without audit documentation, the footage's reliability is questioned.

In Regulatory Audits: A compliance audit requires evidence of access controls. The system can show footage of access points, but cannot provide comprehensive logs of who accessed the surveillance system itself, what they did, and when. The audit fails because the evidence of control is missing.

In Legal Proceedings: A case goes to court. The surveillance footage is offered as evidence. The opposing counsel asks: "How do we know this footage hasn't been modified? What mechanism prevents tampering? Can you prove this is the original footage?" If the system has no integrity verification mechanism, no digital signature, no hash verification, the footage's admissibility is challenged. The judge may exclude it entirely.

In Insurance Claims: Multiple parties dispute what happened. Each claims the surveillance footage supports their version of events. Without verifiable metadata, without documented chain of custody, without proof that the footage hasn't been edited, the insurance company cannot determine which version is accurate. The claim becomes unresolvable.

The Clarity-Evidence Distinction

The fundamental error underlying the clarity trap is the conflation of two different concepts:

Clarity is an observational quality. It describes how well a human can see detail in an image. It is subjective and context-dependent. A 4K image is clearer than a 1080p image in most viewing contexts.

Evidential Integrity is a legal and technical quality. It describes whether footage can be proven authentic, unaltered, and complete. It is objective and verifiable. It depends on timestamps, integrity checksums, access logs, and chain of custody documentation.

These are orthogonal properties. A system can be high-clarity but low-integrity. It can be lower-clarity but high-integrity. Optimal systems achieve both, but when forced to choose, integrity must take priority. A slightly lower-resolution image that can be proven authentic is more valuable than a crystal-clear image that cannot.

The industry's focus on clarity has created a market where vendors compete on resolution, frame rate, and low-light performance—the visible, easily-marketed features. The market has not yet fully developed mechanisms to compete on integrity, verifiability, and evidence-readiness—the less visible but far more consequential features.

What This Guide Will Answer

This chapter has identified the problem: the industry's misdirection toward clarity at the expense of evidence integrity. The remaining chapters answer the critical questions this creates:

- What does "traceability" actually mean in the context of surveillance systems?

- What are the real costs when footage cannot be verified as evidence?

- What are the five key dimensions of an evidence-ready surveillance system?

- How do systems optimized for clarity compare to systems optimized for evidence integrity?

- What practical steps can be taken to implement evidence-ready surveillance?

- How can the investment in evidence integrity be quantified and justified?

- How can evidence-ready systems be verified and maintained over time?

By addressing these questions systematically, this guide provides the framework for transforming surveillance systems from observation tools into reliable evidence platforms.